What is the Rotator Cuff?

And why do Physios care about it so much?

by Pamela Wolfe27 Jul 2025

I’m sure you’ve all heard of the rotator cuff and how important it is to keep it strong. But do we really know why it is so important?

In this blog I am going to take you through the fundamentals of our shoulder anatomy and biomechanics, and the role of the rotator cuff in shoulder health and function. We will discuss what happens if there is a muscle imbalance or a mismatch in strength between the major shoulder muscles. This blog post will help you understand why you may be getting shoulder pain, even though you’re training regularly in the gym.

And lastly, we will discuss the long-term ramifications if the rotator cuff isn’t strengthened and maintained over time.

Anatomy of the Shoulder joint

The shoulder joint is where the head of the humerus articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. It is also referred to as the glenohumeral joint. It is one of the most mobile joints in our body, but as a trade-off for its mobility, it is also one of the most unstable. The glenoid labrum plays a big role in helping to stabilise the joint. The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous rim that deepens the fossa to allow the head of the humerus to sit more securely.

Surrounding the shoulder joint are ligaments that add passive stability to the joint - these include the glenohumeral ligaments; Coracoacromial ligament and Coracoclavicular ligaments.

Other structures to mention that comprise the anatomy of the shoulder are bursae. These are small fluid-filled sacs that reduce friction between bones and soft tissues. The subacromial bursa is the most prominent, cushioning the rotator cuff tendons under the acromion.

And finally, we have nerves and blood vessels that innervate and supply blood to the shoulder. The major nerves stem from the Brachial plexus: A network of nerves that innervates the shoulder and arm. The axillary nerve, suprascapular nerve, and others provide motor and sensory function. The blood supply comes primarily from the subclavian and axillary arteries. In addition to the labrum and the ligaments which provide passive stability to our shoulder joint, we also have tendons which attach muscles to the bones. These muscles provide active stability - the most significant of these muscles is the rotator cuff. We will discuss the role of the rotator cuff and its significance in shoulder health and function later.

Function

Our Shoulder joint is capable of lots of different movements such as flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, and circumduction, making it one of the most mobile—and least stable—joints in the body.

When it comes to the function and mobility of our shoulder complex, the movement of our scapula around the thorax (scapulothoracic motion) can’t be overlooked.

The scapula plays a fundamental role in the positioning and function of the shoulder joint. It moves in multiple directions—elevation, depression, protraction, retraction, upward rotation, and downward rotation—to allow a wide range of arm movements. The scapula serves as the foundational support structure for the shoulder joint. It ensures proper alignment, mobility, and force transmission during upper limb movements. Healthy shoulder function depends heavily on proper scapular control and motion.

Correct Scapulohumeral rhythm—the coordinated movement between the scapula and humerus— is essential for full and pain-free arm elevation (i.e. raising your arm above your head). Muscles like the trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids, and rotator cuff muscles anchor the scapula and support shoulder movements. Shoulder pain, injury and / or surgery can often cause a dysfunction in this rhythm and the muscles responsible for it.

What is the Rotator Cuff and what does it do?

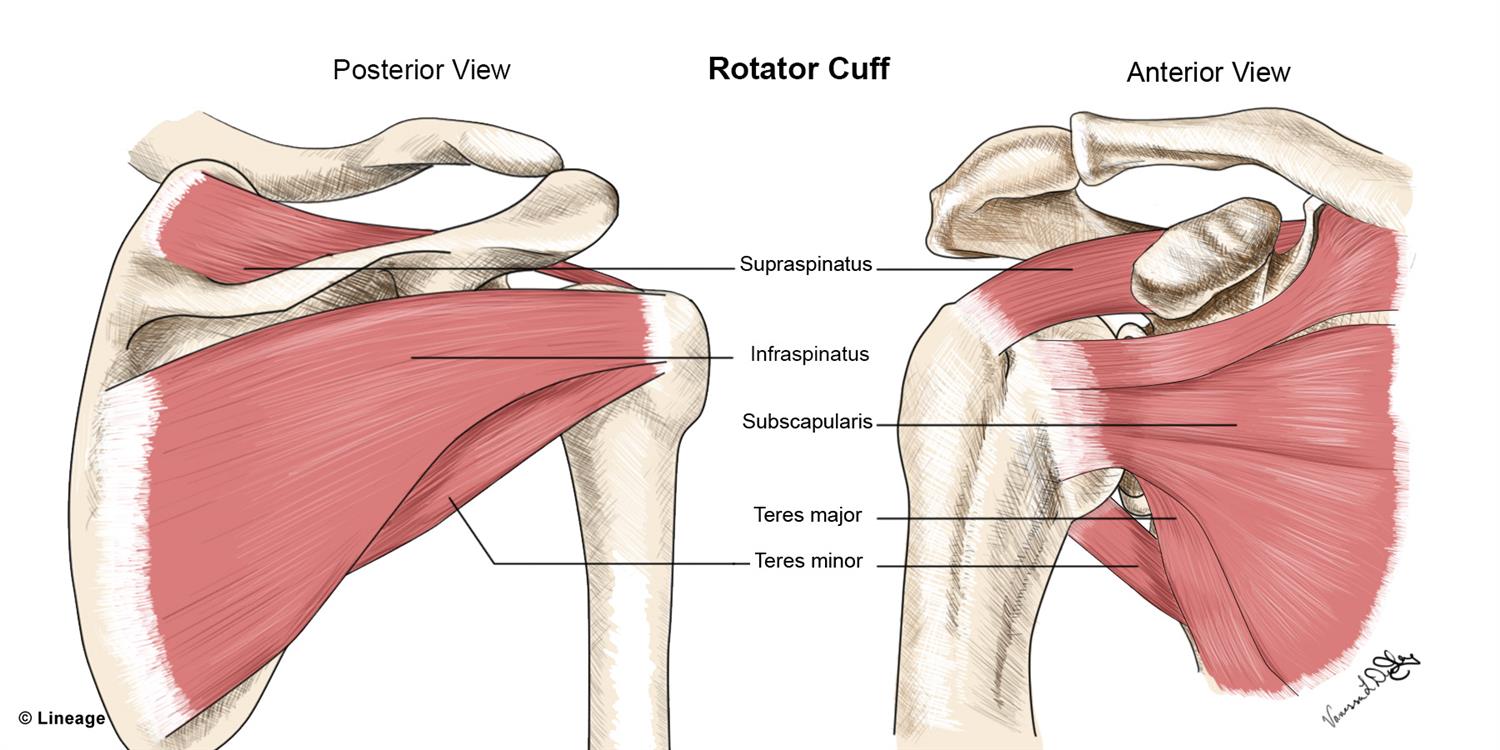

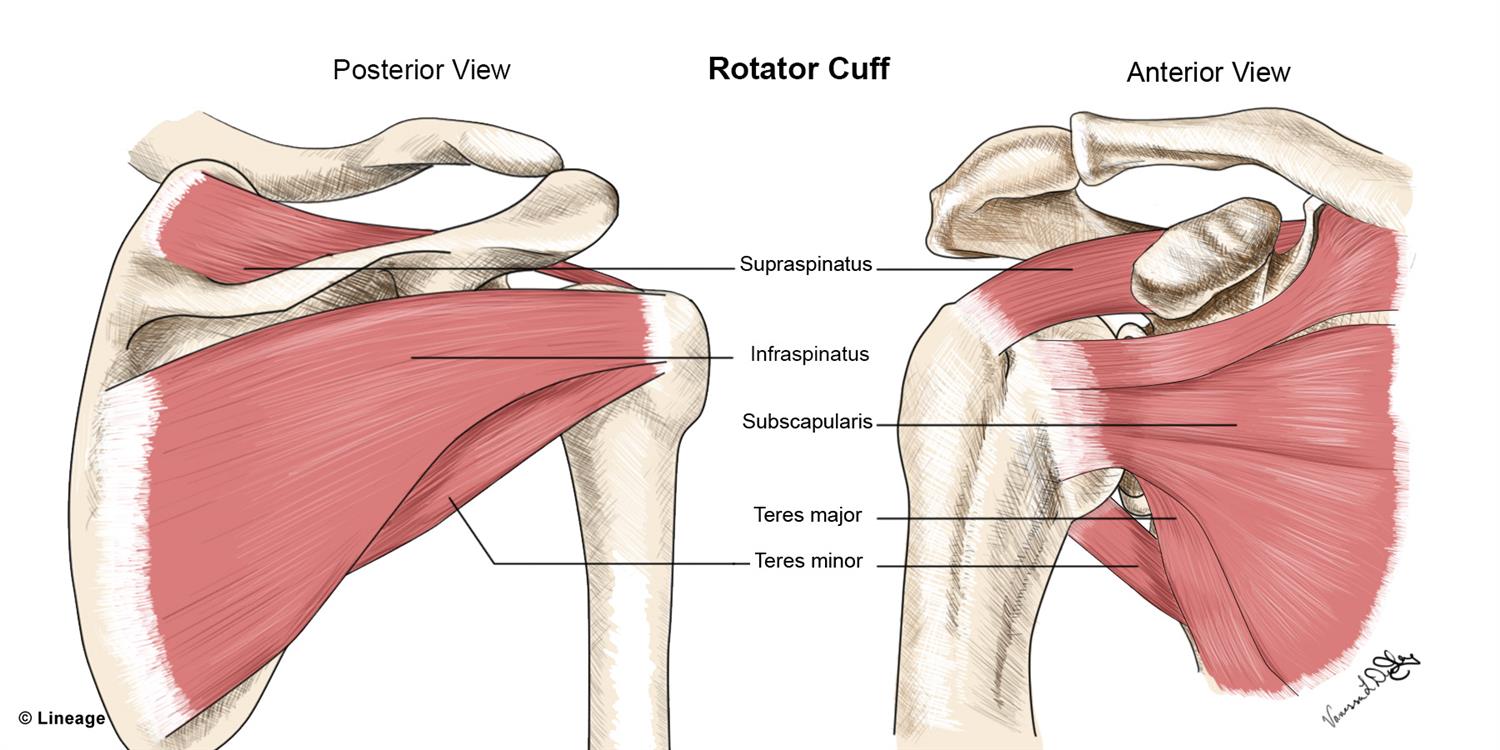

The rotator cuff is a group of 4 muscles that surround and support the glenohumeral joint. The most important job of the rotator cuff is keeping the humeral head centered and secure within the glenoid cavity during movements of the shoulder. Individually each muscle also has directional movement functions:

• Supraspinatus: this muscle sits above the spine of the scapula and assisted to abduct the arm in the initial 30 degrees.

• Infraspinatus: this muscle is located below the spine of the scapula, its primary role is to externally rotate the humerus.

• Teres minor: Sits just below infraspinatus, it also contributes to externally rotating the humerus.

• Subscapularis: This is located at the front of the shoulder blade and is responsible for internal rotation of the shoulder.

This group of muscles and their tendons surround the GH joint and provide dynamic stability and movement. They work concurrently to prevent dislocations and unwanted translations of the humerus within the glenoid cavity.

In addition to their important role as stabilisers, they are also responsible for control and smooth movement of the shoulder joint during tasks such as throwing, lifting, reaching etc. The rotator cuff muscles work in co-ordination with larger more powerful muscles such as our deltoids, pectoralis major, and trapezius muscles.

What happens if there is an imbalance in strength between our rotator cuff and the larger, more powerful muscles of the shoulder?

In this next section we are going to discuss what happens within the shoulder joint when there is a mismatch in strength between the big muscles (deltoid, pec, traps) surrounding the shoulder and the rotator cuff.

1. Reduced Shoulder Stability.

As we know, the rotator cuff is responsible for keeping the humeral head centered and secure within the glenoid cavity during movements of the shoulder.

If the rotator cuff is weaker compared to the bigger muscles (such as deltoid, pec major, and latissimus dorsi), this can lead to the larger muscles overpowering the rotator cuff and pulling the joint out of optimal alignment.

This can lead to superior and anterior translation of the humeral head which can lead to narrowing of the subacromial space and subsequent impingement.

2. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

As the humeral head moves incorrectly, it can pinch the rotator cuff tendons or bursa under the acromion (within the subacromial space) This leads to inflammation, pain, and reduced range of motion—especially during overhead activities.

3. Overuse and Injury

If the rotator cuff is not strong or conditioned enough to withstand the demand we put it under through our sport, exercise, lifestyle etc, it can become overloaded trying to stabilize the joint. Over time, this can result in injuries such as tendinitis, tears, bursitis, and degenerative changes within the shoulder joint.

4. Compensatory Movement and Postural Changes

The body may compensate by recruiting other muscles (like upper traps or neck muscles), leading to poor posture, muscle fatigue, or neck and upper back pain.

5. Decreased Performance

In athletes or active individuals, this imbalance can reduce strength, accuracy, and endurance. More commonly in throwing athletes, swimmers, or lifters—where shoulder control is essential.

The rotator cuff provides precision and control, while larger muscles generate power and movement. If one overpowers the other, the whole shoulder system suffers.

Why, even though we go to the gym regularly, do we still get shoulder pain?

Now let's try to answer a very common question and problem we see in our clinic…. Why do I still get shoulder pain even though I regularly train my upper body in the gym?

1. Unbalanced training

Too much focus on the big powerful muscles (such as deltoid, latissimus dorsi, pec major), and not enough focus on the small stabilising muscles of the shoulder joint and scapula (such as serratus anterior, lower traps, rhomboids and rotator cuff).

Without strong stabilisers, the shoulder joint lacks control, leading to impingement or instability—especially during heavy lifts like bench press or shoulder press.

2. Poor shoulder biomechanics

Suboptimal movement patterns can lead to complications such as rotator cuff strain, joint misalignment, pinching of tendons or bursa Over time, this leads to inflammation and chronic pain.

3. Reduced Mobility and Flexibility

Tight muscles (like pec minor or lats) and stiff joints reduce range of motion, leading to compensation and suboptimal biomechanics. Which can lead to increased stress on the rotator cuff and joint surfaces of the shoulder.

4. Imbalanced Push-Pull Training

Many lifters overdo pushing exercises (bench, pushups, shoulder press) and undertrain pulling (rows, face pulls, external rotations). This creates muscular imbalances and leads to poor scapular positioning, which is key for optimal shoulder movement.

5. Ignoring Warm-Up and Activation

Jumping straight into heavy pressing without warming up or activating the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers increases injury risk. The shoulder needs proper activation for stability during compound lifts.

5. Previous Injuries or Poor Recovery

Old shoulder injuries, if not properly rehabilitated, can leave behind weaknesses or scar tissue that flare up during intense training.

What are some of the long term ramifications of not strengthening your rotator cuff?

1. Shoulder Instability

The rotator cuff stabilises and controls the shoulder joint during movement. If the rotator cuff isn’t strong enough to do its job properly, this can lead to instability at the shoulder. Over time, this can lead to microtrauma to other joint structures and an increased risk of partial or full dislocations.

2. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

Weaker rotator cuff muscles fail to control the humeral head optimally. This allows the humeral head to ride up and compress/impinge on soft tissues that sit within the sub-acromial space. These tissues can get inflamed and painful with time. The most common signs and symptoms of this include pain when lifting your arm, pain when lying on that shoulder at night, and weakness in the overhead position.

3. Rotator Cuff Tears

Ongoing weakness and poor mechanics lead to tendon wear. Small strains or micro tears accumulate over time and can develop into degenerative tears, not just traumatic ones. These occur more commonly with age and/or repetitive use. These can be symptomatic or asymptomatic.

4. Loss of Range of Motion

Weaker rotator cuff muscles, coupled with joint irritation for suboptimal mechanics can overtime lead to reduced shoulder mobility. As a result, some everyday tasks can become much more challenging due to weakness and limited range of motion.

5. Compensatory Injuries

When the rotator cuff can’t stabilize the joint, other muscles (like the upper traps, neck muscles, or pecs) step in. This may lead to imbalances, overloading, tightness and reduced flexibility of these muscles. This can in some cases contribute to neck and upper back pain.

6. Arthritis and Joint Degeneration

Poor rotator cuff function can over time lead to excessive joint wear and cartilage breakdown. Over decades, this can result in glenohumeral osteoarthritis.

7. Reduced Athletic Performance

Weak rotator cuff = poor shoulder control = less power, precision, and endurance. It can particularly affect people partaking in throwing sports, swimming, weightlifting, tennis golf.

Take home message

Take home message The rotator cuff is a small, often neglected, but critically important group of muscles. It is fundamental in the overall functioning of the shoulder. Strengthening our rotator cuff can reduce our risk of injury, it enhances performance and helps to keep our shoulders pain-free and functioning well over time so that we can continue to do the sports, exercise, and activities we love.

In this blog I am going to take you through the fundamentals of our shoulder anatomy and biomechanics, and the role of the rotator cuff in shoulder health and function. We will discuss what happens if there is a muscle imbalance or a mismatch in strength between the major shoulder muscles. This blog post will help you understand why you may be getting shoulder pain, even though you’re training regularly in the gym.

And lastly, we will discuss the long-term ramifications if the rotator cuff isn’t strengthened and maintained over time.

Anatomy of the Shoulder joint

The shoulder joint is where the head of the humerus articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. It is also referred to as the glenohumeral joint. It is one of the most mobile joints in our body, but as a trade-off for its mobility, it is also one of the most unstable. The glenoid labrum plays a big role in helping to stabilise the joint. The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous rim that deepens the fossa to allow the head of the humerus to sit more securely.

Surrounding the shoulder joint are ligaments that add passive stability to the joint - these include the glenohumeral ligaments; Coracoacromial ligament and Coracoclavicular ligaments.

Other structures to mention that comprise the anatomy of the shoulder are bursae. These are small fluid-filled sacs that reduce friction between bones and soft tissues. The subacromial bursa is the most prominent, cushioning the rotator cuff tendons under the acromion.

And finally, we have nerves and blood vessels that innervate and supply blood to the shoulder. The major nerves stem from the Brachial plexus: A network of nerves that innervates the shoulder and arm. The axillary nerve, suprascapular nerve, and others provide motor and sensory function. The blood supply comes primarily from the subclavian and axillary arteries. In addition to the labrum and the ligaments which provide passive stability to our shoulder joint, we also have tendons which attach muscles to the bones. These muscles provide active stability - the most significant of these muscles is the rotator cuff. We will discuss the role of the rotator cuff and its significance in shoulder health and function later.

Function

Our Shoulder joint is capable of lots of different movements such as flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, and circumduction, making it one of the most mobile—and least stable—joints in the body.

When it comes to the function and mobility of our shoulder complex, the movement of our scapula around the thorax (scapulothoracic motion) can’t be overlooked.

The scapula plays a fundamental role in the positioning and function of the shoulder joint. It moves in multiple directions—elevation, depression, protraction, retraction, upward rotation, and downward rotation—to allow a wide range of arm movements. The scapula serves as the foundational support structure for the shoulder joint. It ensures proper alignment, mobility, and force transmission during upper limb movements. Healthy shoulder function depends heavily on proper scapular control and motion.

Correct Scapulohumeral rhythm—the coordinated movement between the scapula and humerus— is essential for full and pain-free arm elevation (i.e. raising your arm above your head). Muscles like the trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids, and rotator cuff muscles anchor the scapula and support shoulder movements. Shoulder pain, injury and / or surgery can often cause a dysfunction in this rhythm and the muscles responsible for it.

What is the Rotator Cuff and what does it do?

The rotator cuff is a group of 4 muscles that surround and support the glenohumeral joint. The most important job of the rotator cuff is keeping the humeral head centered and secure within the glenoid cavity during movements of the shoulder. Individually each muscle also has directional movement functions:

• Supraspinatus: this muscle sits above the spine of the scapula and assisted to abduct the arm in the initial 30 degrees.

• Infraspinatus: this muscle is located below the spine of the scapula, its primary role is to externally rotate the humerus.

• Teres minor: Sits just below infraspinatus, it also contributes to externally rotating the humerus.

• Subscapularis: This is located at the front of the shoulder blade and is responsible for internal rotation of the shoulder.

This group of muscles and their tendons surround the GH joint and provide dynamic stability and movement. They work concurrently to prevent dislocations and unwanted translations of the humerus within the glenoid cavity.

In addition to their important role as stabilisers, they are also responsible for control and smooth movement of the shoulder joint during tasks such as throwing, lifting, reaching etc. The rotator cuff muscles work in co-ordination with larger more powerful muscles such as our deltoids, pectoralis major, and trapezius muscles.

What happens if there is an imbalance in strength between our rotator cuff and the larger, more powerful muscles of the shoulder?

In this next section we are going to discuss what happens within the shoulder joint when there is a mismatch in strength between the big muscles (deltoid, pec, traps) surrounding the shoulder and the rotator cuff.

1. Reduced Shoulder Stability.

As we know, the rotator cuff is responsible for keeping the humeral head centered and secure within the glenoid cavity during movements of the shoulder.

If the rotator cuff is weaker compared to the bigger muscles (such as deltoid, pec major, and latissimus dorsi), this can lead to the larger muscles overpowering the rotator cuff and pulling the joint out of optimal alignment.

This can lead to superior and anterior translation of the humeral head which can lead to narrowing of the subacromial space and subsequent impingement.

2. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

As the humeral head moves incorrectly, it can pinch the rotator cuff tendons or bursa under the acromion (within the subacromial space) This leads to inflammation, pain, and reduced range of motion—especially during overhead activities.

3. Overuse and Injury

If the rotator cuff is not strong or conditioned enough to withstand the demand we put it under through our sport, exercise, lifestyle etc, it can become overloaded trying to stabilize the joint. Over time, this can result in injuries such as tendinitis, tears, bursitis, and degenerative changes within the shoulder joint.

4. Compensatory Movement and Postural Changes

The body may compensate by recruiting other muscles (like upper traps or neck muscles), leading to poor posture, muscle fatigue, or neck and upper back pain.

5. Decreased Performance

In athletes or active individuals, this imbalance can reduce strength, accuracy, and endurance. More commonly in throwing athletes, swimmers, or lifters—where shoulder control is essential.

The rotator cuff provides precision and control, while larger muscles generate power and movement. If one overpowers the other, the whole shoulder system suffers.

Why, even though we go to the gym regularly, do we still get shoulder pain?

Now let's try to answer a very common question and problem we see in our clinic…. Why do I still get shoulder pain even though I regularly train my upper body in the gym?

1. Unbalanced training

Too much focus on the big powerful muscles (such as deltoid, latissimus dorsi, pec major), and not enough focus on the small stabilising muscles of the shoulder joint and scapula (such as serratus anterior, lower traps, rhomboids and rotator cuff).

Without strong stabilisers, the shoulder joint lacks control, leading to impingement or instability—especially during heavy lifts like bench press or shoulder press.

2. Poor shoulder biomechanics

Suboptimal movement patterns can lead to complications such as rotator cuff strain, joint misalignment, pinching of tendons or bursa Over time, this leads to inflammation and chronic pain.

3. Reduced Mobility and Flexibility

Tight muscles (like pec minor or lats) and stiff joints reduce range of motion, leading to compensation and suboptimal biomechanics. Which can lead to increased stress on the rotator cuff and joint surfaces of the shoulder.

4. Imbalanced Push-Pull Training

Many lifters overdo pushing exercises (bench, pushups, shoulder press) and undertrain pulling (rows, face pulls, external rotations). This creates muscular imbalances and leads to poor scapular positioning, which is key for optimal shoulder movement.

5. Ignoring Warm-Up and Activation

Jumping straight into heavy pressing without warming up or activating the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers increases injury risk. The shoulder needs proper activation for stability during compound lifts.

5. Previous Injuries or Poor Recovery

Old shoulder injuries, if not properly rehabilitated, can leave behind weaknesses or scar tissue that flare up during intense training.

What are some of the long term ramifications of not strengthening your rotator cuff?

1. Shoulder Instability

The rotator cuff stabilises and controls the shoulder joint during movement. If the rotator cuff isn’t strong enough to do its job properly, this can lead to instability at the shoulder. Over time, this can lead to microtrauma to other joint structures and an increased risk of partial or full dislocations.

2. Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

Weaker rotator cuff muscles fail to control the humeral head optimally. This allows the humeral head to ride up and compress/impinge on soft tissues that sit within the sub-acromial space. These tissues can get inflamed and painful with time. The most common signs and symptoms of this include pain when lifting your arm, pain when lying on that shoulder at night, and weakness in the overhead position.

3. Rotator Cuff Tears

Ongoing weakness and poor mechanics lead to tendon wear. Small strains or micro tears accumulate over time and can develop into degenerative tears, not just traumatic ones. These occur more commonly with age and/or repetitive use. These can be symptomatic or asymptomatic.

4. Loss of Range of Motion

Weaker rotator cuff muscles, coupled with joint irritation for suboptimal mechanics can overtime lead to reduced shoulder mobility. As a result, some everyday tasks can become much more challenging due to weakness and limited range of motion.

5. Compensatory Injuries

When the rotator cuff can’t stabilize the joint, other muscles (like the upper traps, neck muscles, or pecs) step in. This may lead to imbalances, overloading, tightness and reduced flexibility of these muscles. This can in some cases contribute to neck and upper back pain.

6. Arthritis and Joint Degeneration

Poor rotator cuff function can over time lead to excessive joint wear and cartilage breakdown. Over decades, this can result in glenohumeral osteoarthritis.

7. Reduced Athletic Performance

Weak rotator cuff = poor shoulder control = less power, precision, and endurance. It can particularly affect people partaking in throwing sports, swimming, weightlifting, tennis golf.

Take home message

Take home message The rotator cuff is a small, often neglected, but critically important group of muscles. It is fundamental in the overall functioning of the shoulder. Strengthening our rotator cuff can reduce our risk of injury, it enhances performance and helps to keep our shoulders pain-free and functioning well over time so that we can continue to do the sports, exercise, and activities we love.

B.Sc (Hons) Physio, B.Sc.HPS, APAM

Senior Physiotherapist

Senior Physiotherapist